What We've Learned From the POST Records (So Far)

For those just joining us: my other endeavor, The Bramanville Tribune, tried to get the Police Officers Standards and Training Commission (POST) law enforcement complaint spreadsheets from each municipality in the commonwealth. The police departments fought back, hard, but, with some exceptions as of now, the state has strongarmed the towns and cities into providing the records.

The question that kept rolling through my mind as I filed appeal after appeal after appeal was "what on earth are they trying to hide?" Transparency is easy. Law enforcement flouting public records law less so. Many departments learned this the hard way, others didn't even try to protest, but the outcome? As of today, the first real day of this new endeavor, approximately 200 municipalities have sent me the POST records they sent to the state last year. You can find your municipality here, along with some details on how they did (or didn't) comply.

What have we learned?

Most police records are boring

Far too many records left me wondering why they fought so hard against disclosure in the first place.

Take for example, Brimfield. The town of Brimfield started out with giving me the same canned language from the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association (MCOPA) that so many other municipalities did. The records show a very dull existence in terms of law enforcement misconduct, with one single reported complaint that resulted in a verbal reprimand. Why was that worth going through the motions of an appeal?

Countless towns had similar issues - few or no complaints to speak of, easy transparency, and yet here we are. I can't imagine how much additional time and money was wasted, both from the departments and the state, in dealing with these appeals and efforts to withhold public records. And then to put that much time and money into withholding records that make your police department look good.

I'm not dumb. This is at least partially some version of the Blue Wall of Silence, where these chiefs of police want to back "their guys" and don't want to expose the minor infractions as something bigger. A few chiefs of police I spoke with said as much - to paraphrase, one was concerned about uniform violations and what have you getting reported out as "problem cops." Others, though, it was expressly clear that they were withholding the records either because it made their departments look bad or worse.

Perhaps, someday, I'll be able to cross-reference the experience of the chiefs that were the most resistant with their familiarity with the unions or role as officers or what have you. Still, based on some emails that I was able to successfully procure, it's probably partially a version of "everybody else is doing it, so why can't we?"

MCOPA is a menace

Many of the problems of police transparency in this state appear to sit at the doorstep of the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association.

In roughly a week, your local department may spend anywhere from $200-500 per officer to get a lesson on public records from someone who functionally lost more 200 appeals based on his shoddy advice. If not this week, they very well might spend this money at a different records training, or at some other MPI workshop.

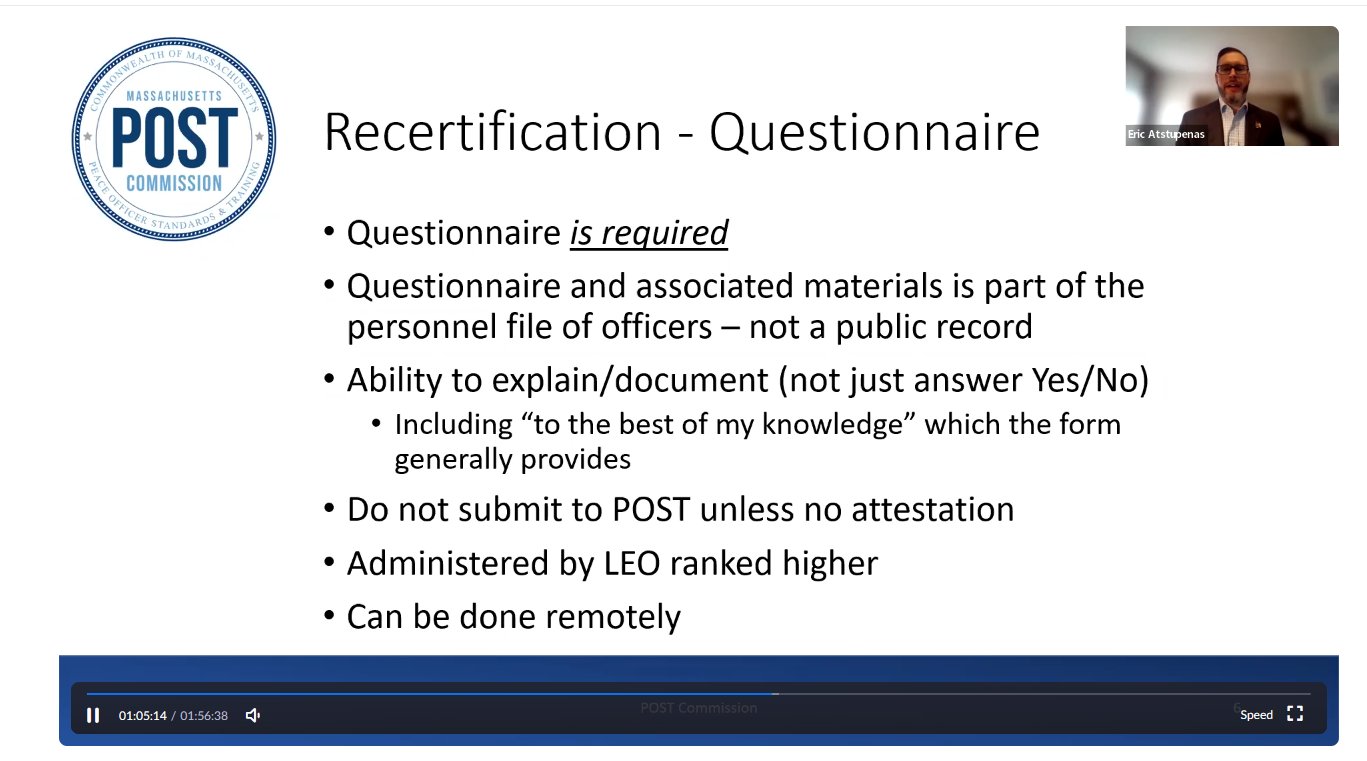

MCOPA legal counsel Eric Atstupenas provided the language that destroyed my inbox for a month, where he relied on an irrelevant lawsuit and specious reasons to deny records, and even pushed POST to act in service of restricting the records (fast forward to 1:05:00 - story on this meeting coming soon).

I reached out to Atstupenas in April for this story, and he did not want to comment. In his Guide to Public Records for Massachusetts Public Safety Personnel - 2022 Edition, the most recent edition of which he provides free of charge to MCOPA membership as part of his newsletter, he writes:

All records a police department holds, creates, maintains, etc. are presumed to be public records unless a specifically identified exemption applies. “G.L. c. 66, section 10 imposes a presumption that the record sought is public and places the burden on the records custodian to ‘prove with specificity’ that an exemption applies.”

To his credit, in his initial email, he did admit that most of the POST spreadsheet records would be public, but it didn't stop him from sending a script to his MCOPA membership with something to throw against the wall. To me, a responsible advocate for the departments and the interests of the chiefs of police would simply give the explanation as to why the records are public and why the chiefs should comply. Instead, we got this.

200+ appeals later? We reached the "find out" stage.

On page 83 of his guide, he writes:

Based upon the new language of exemption (c) and the Worcester Telegram & Gazette decision, the following records may not automatically be held in their entirety under exemption (c):

-> Citizen complaints

-> Notice of claim under the Tort Claims Act

-> Letters from the Chief to the complainant (advising of the start of the investigation and of its results)

-> Police reports

-> Incident reports

-> Arrest logs

-> Memoranda from the Chief to the involved officer and other officers requiring information about the incident

-> Responses of the involved officer and other officers

-> Summaries of witness interviews

-> Internal affairs report and supplemental report

-> Memorandum from the Chief to the involved officer detailing the results of the investigation

-> Notice from the disciplining authority to the involved officer advising of the disciplinary decision.

The fact that a complaint does not allege criminal activity or is brought by a member of the force – as opposed to a private citizen – does not allow the record to be withheld under exemption (c).

Exemption (c) may not be used to withhold the internal affairs investigation report into a “non-uniformed civilian” police employee.

What's telling here is that Atstupenas buries the lede to some extent. Exemption (c) was rewritten in 2020 specifically to make these records public, and the police departments know it. These are the records that the legislature wanted to have available for public review, and unless Atstupenas's 2021 update made it clear, not providing that context is a significant miss. The exemption's language could not be clearer: "...this subclause shall not apply to records related to a law enforcement misconduct investigation."

It is crazy that I, a citizen journalist and village idiot, can grasp what "shall not apply" means, but someone paid to be a legal expert and who gives classes on public records compliance will give advice to tapdance around it and hope no one pushes back. It is maddening to me that the Municipal Police Institute (MPI) will likely take in thousands of dollars - of your tax dollars, after taking hundreds (if not thousands) of dollars in labor costs to not comply with public records requests - to an organization (MPI, which is an affiliate of MCOPA) that did them so wrong for a class presented by the person who caused them this many problems.

(Stay tuned for the next MassTransparency project rolling out later this week related to this particular issue.)

Transparency provides context

A lesson in five incidents

One municipality, in its response to me, said that these records didn't have any real public interest, and POST's misguided choice to not publicize them was proof. As I sorted through the records I received, however, other stories of police conduct made their way through the media. It became a habit of mine to check on the records for the officers in hot water and see if it told us anything interesting. As always, people are innocent until proven guilty, but, for example:

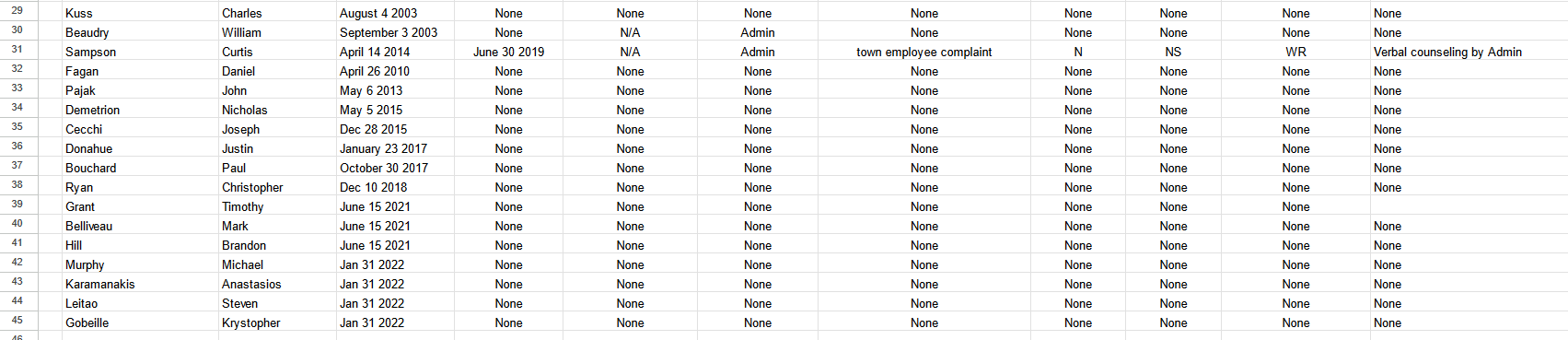

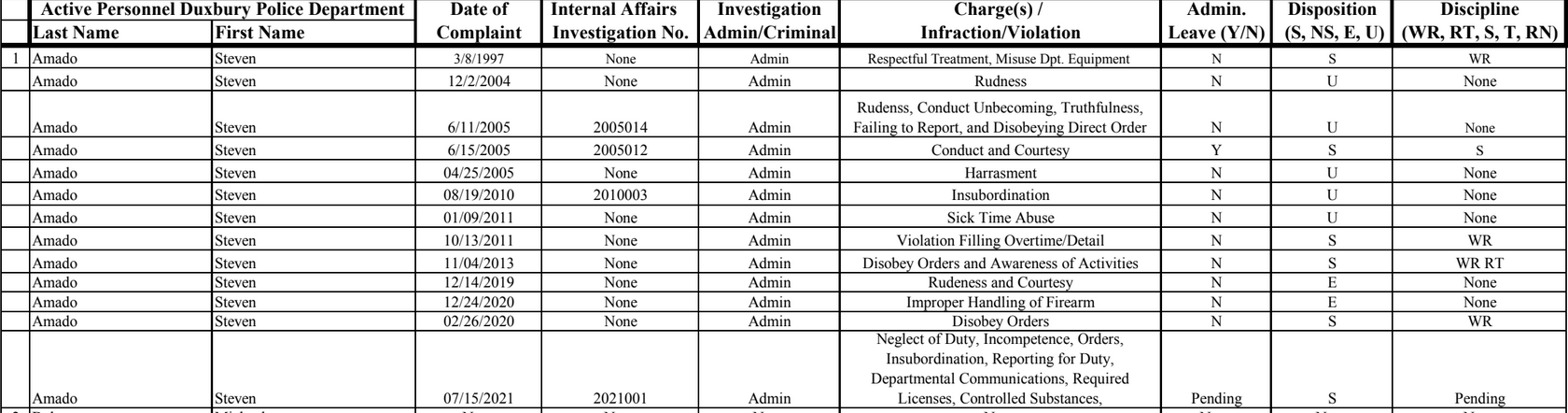

- In Duxbury, Steven Amado was indicted on charges of falsifying a police report and witness intimidation. The Boston Globe, who I believe broke the story, describes Officer Amado as "a 24-year veteran of the force." Duxbury's POST records, in contrast (which, by the way, I had to appeal to the state to get), show an officer with 13 prior reported incidents, six of which were sustained. Prior to this year, there was no immediate way for the people of Duxbury or anyone who gets to visit their beaches to know that one officer makes up nearly half of the reported incidents in the town. I completely understand why the Duxbury chief wouldn't want this public, because that's a real condemnation of the department that kept letting this officer get away with it. But why wouldn't POST want people to know this?

- In Douglas, Officer Brett Fulone (who you may have seen on Good Morning America with the department K-9) was demoted following five sustained infractions in 2015 that include "Incompetence," "Truthfulness," and "Care and Security of Dept. Firearms," as well as a sustained 2017 incident labeled "Accidental Firearm Discharge." Officer Fulone currently serves as the Douglas School Resource Officer.

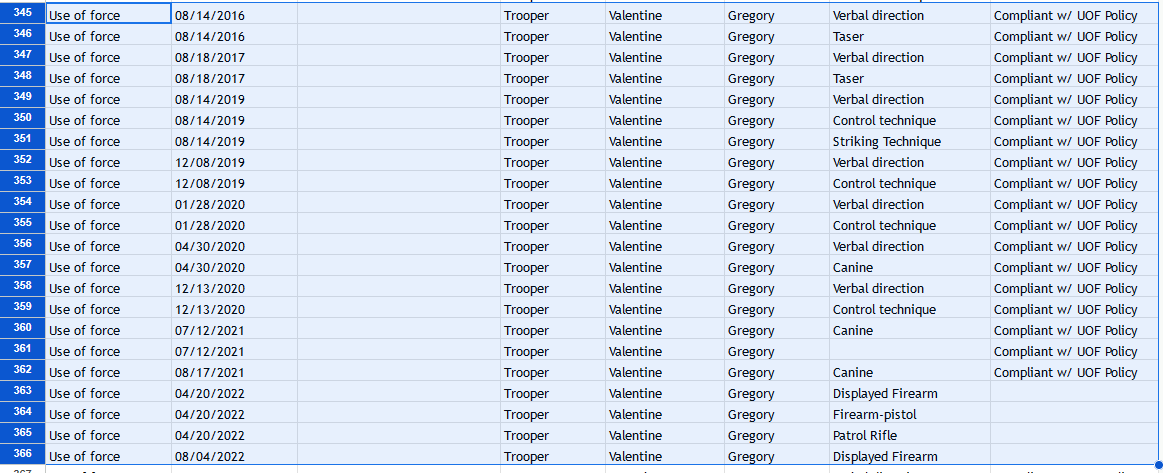

- The Massachusetts State Police had a headline-worthy drug bust recently. Trooper Gregory Valentine, the K-9 officer involved in the bust, has a host of use-of-force complaints. That at least makes me look at the press release a little differently. (Note: the State Police spreadsheets come from Andrew Quemere of The Mass Dump, which you should be reading.)

- In Lawrence, Captain Michael Mangan was placed on administrative leave following a use-of-force incident allegedly caught on camera. Lawrence's POST records tell a story of a captain who was accused of excessive force ten years prior (and said incident was not sustained) in a department rife with disciplinary problems.

- It works in the other direction, too. Dighton Chief of Police Shawn Cronin was indicted by the Securities and Exchanges Commission this week on allegations of securities and tender offer fraud. Not only was Chief Cronin good-natured and friendly in my interactions with him in getting Dighton's record, but his record was spotless, too. Wouldn't have seen that coming, but now I wish I asked for stock tips.

These are just the stories I found. Imagine what else people who know about circumstances in their own hometowns might find. This database would have provided the public with unprecedented ability to connect dots previously unavailable to them, and the POST Commission decided to say "nah."

As of the time of this writing, I'm looking at approximately 100 appeals in flight. I do plan to eventually turn this into a workable database with annual updates, but that is a longer-term process (unless someone with business intelligence acumen wants to give some time to this project...). As it stands, though, the firehose of content is available to the public for all to review, and I am looking forward to seeing what other information can be gleaned from the data.

Jeff Raymond is a former columnist for the Millbury-Sutton Chronicle and Founding Editor of The Bramanville Tribune. He can be reached at jeff.raymond@masstransparency.org or on Twitter at @jeffinmillbury